Analyzing South Africa's Controversial 4G Wholesale PlanAnalyzing South Africa's Controversial 4G Wholesale Plan

Guy Zibi from Xalam Analytics takes stock of South Africa's proposed 4G wholesale experiment and how it could impact multiple markets.

Last November, the South African government approved the Electronics Communications Amendment (ECA) Bill, kicking off the process to update the governing law for the country's information and communications technology (ICT) sector.

The proposed Bill, if enacted, would be arguably the most pivotal piece of legislation to come to the South African telecoms market since 2005. It would provide the legal framework that will underpin the growth of 4G, 5G, IoT and other new technologies in the market, for at least the next 10 years.

Ripples beyond South Africa

The ripple effects of the new ICT law will be felt beyond South Africa. The country is Africa's largest ICT market, and the primary point of entry for international firms seeking to penetrate the continent. South African tech firms and investors are among the largest sources of ICT sector investment in Africa.

Around 30% and 90% respectively of the free cash flows of the MTN and Vodacom groups (excluding Safaricom) are generated in South Africa. At a time when more international players are looking for exit doors, the two companies need a home base that is large enough to generate the free cash flows to finance pan-African adventures.

The new law has been controversial -- most notably for its contentious proposal to establish a 4G Wholesale Open-Access Network (WOAN) and suggestions to claw back spectrum held by existing mobile players. We discuss those below, but we argue that the proposed Bill cannot be optimally appreciated, nor its shortcomings addressed, without a clear understanding of the essence of what's driving it.

When a successful market fails

South Africa is a paradox. By many measures, this is a thriving, and mostly successful, telecoms market -- Africa's largest in terms of revenues, smart device connections, FTTH and 4G. South African telecoms operators are among the most successful in Africa, in terms of revenues and profitability. Headline service penetration numbers are high; mobile SIM penetration of the population is around 160% (~95% on a unique user basis) and mobile broadband penetration is close to 75%.

And yet, the South African ICT market also has serious failings. Digital divides are stark, between urban and rural areas, and between rich and poor. A recent survey by World Wide Worx and Dark Fibre Africa estimated that nearly half of South African adults did not have access to the Internet in 2017. Fiber deployments have been concentrated in business districts and upper middle-class neighborhoods.

The mobile market is highly concentrated; the two largest players, Vodacom and MTN, control around 80% of sector revenue, and nearly 90% of the sector's operating income. Data pricing models penalize lower-end users, with South African operators clinging to an antiquated 'out-of-bundle' model that charges a premium outside of a set data package.

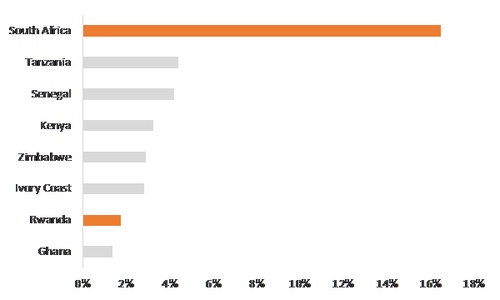

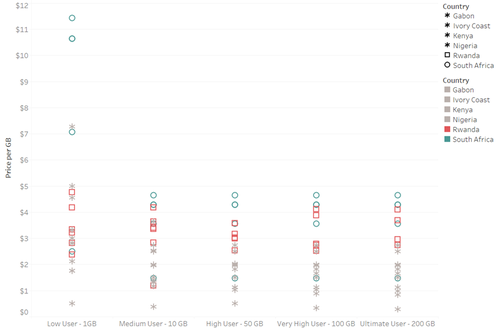

Our own data pricing benchmarks and recent data affordability estimates by the Alliance for Affordable Internet (A4Ai) suggest that South African mobile data prices are among the highest in Africa. Indeed, the outcry around data prices has been so loud that the movement now has its own trending hashtag on Twitter, #datamustfall.

This is a system that, in effect, has delivered for the mid to upper-middle class -- but outside of basic voice and some community services, still largely fails the lower-income segments of the population. In a country where slightly more than half of the population lives under the poverty line, this looms large.

At the heart of the proposed ICT law is thus a battle over the approach to resolve these market failings: Add to that a sprinkle of recrimination about concentration of power and capital, ideological differences about the role of the state in the economy and the potential of impending government change, and you have the makings of a highly complicated equation.

Source: Xalam Analytics research, based on operator pricing data; based on 4G packages by 35 operators in 12 African markets; pricing as of December 2017; packages with validity of 30 days or more.

SA's proposed new law -- a monstrous mishmash

Most of the concerns around data prices and market concentration are legitimate. The suggested approach to resolving them, however, may well do more harm than good. Like most attempts to do many complicated things at the same time, the new bill is a monstrous mishmash of the desire to extend connectivity to the unconnected, satisfy the urgent demand for 4G spectrum, break the control of the top three telecoms operators in the market, transfer regulatory control away from the regulator and back to the Minister of Telecoms, and give the state more say into telecoms operations.

That can't end well. Consider a few of the Bill’s proposals:

Bring on the WOAN

The ECA Bill's objective to establish a wholesale open access network (WOAN) is arguably its most controversial feature. Under the proposal, most of the high-demand spectrum would be allocated to the WOAN. The WOAN would then sell access to its network on an open-access basis, in theory pushing competition away from the infrastructure layer and into the service layer. Once the WOAN is "functional" (a phase that remains to be defined), the balance of the spectrum would be allocated to existing operators. Existing players would also be required to acquire at least 30% of their spectrum from the WOAN.

On paper, a public-private partnership WOAN is not an inherently terrible idea. The open access concept has been used with some success in segments where private players have been reluctant to invest, notably in the terrestrial fiber space (but with some resounding failures too -- Australia, for example).

Making this work in the 4G wireless space is a lot more complicated. For one, existing players are perfectly willing to invest in 4G. Further, the 4G WOAN model has yet to meet with resounding success. Rwanda's WOAN model has been ineffective in bringing prices down. As a proportion of the mobile SIM base, 4G adoption in Rwanda is one of the lowest among markets that have had 4G services for more than two years, a puzzling performance in a country that is otherwise one of Africa's most dynamic.

Indeed, Rwanda ranks at essentially the same level as South Africa on the latest A4Ai mobile data affordability index. A similar 4G wholesale plan in Russia fell apart. Mexico's WOAN plan is arguably more advanced, but it is not yet operational and its economics are already raising warning signs.

Source: Xalam Analytics research

Perhaps South Africa will be the exception that proves the rule -- but in a market where the government's track record in managing large scale infrastructure assets has been so abysmal, those odds are not compelling.

4G for structural market re-engineering

South Africa's proposed WOAN also comes with a multitude of critical, unanswered questions around a number of issues, including state control (the government says it will be a "private-sector led initiative"), investment capacity, timing, and so on. In the end, ISPs and other stakeholders genuinely interested in cutting down data prices and extending affordable access to the unconnected should be careful what they wish for. They cannot get so fixated with curbing the power of MTN and Vodacom as to lose sight of the core objective of affordable access. The WOAN would curb the power of the incumbents, to be sure. Whether it will drive down data prices and offer affordable data services while operating on an economic basis is less certain.

There are issues beyond the WOAN. For one, the ECA Bill raises substantial concerns around the overall approach to 4G spectrum allocation and management, including a threatening clause to potentially claw back the spectrum held by existing operators when their licence validity expires. Then there are the delays. South Africa has wasted a lot of time already on 4G spectrum allocation. It is one of the few countries in Africa that has yet to allocate 4G spectrum as part of a formal process, a complacency partly borne out of its operators' success in driving 4G growth with refarmed spectrum.

But after nearly five years, close to 15 million 4G connections, and skyrocketing data traffic, operators have pushed the outer limits of spectrum refarming. They need 4G spectrum -- and urgently. And yet, the government's decision to use 4G spectrum as its primary lever to execute a complicated re-engineering of the industry's structure creates doubts that operators will get 4G spectrum in 2018 at all -- a mystifying thought. In a market that needs between US$1.5 billion and $2 billion annually in expanding broadband networks, the uncertainty is crippling.

Declawing the regulator

Finally, and somewhat lost in the shuffle of the debate around the WOAN and 4G, is a fundamental weakening under the ECA Bill of the authority and independence of ICASA, South Africa's regulator. Under the Bill, the Minister of Telecommunications gets to: Decide what constitutes high-demand spectrum; determine spectrum allocations and who gets to pay; and approve rollout and universal service obligations.

At some level, the attempt to declaw ICASA is not surprising -- the regulator and the Ministry have been at loggerheads on a number of critical issues (including 4G spectrum), even battling in court at times. It stands to reason that the Ministry would want to use the new law to render the regulator impotent -- but this is a most alarming development, even more so in a context in which the state aims to play a more interventionist role in the sector.

Which way is out?

There is some way to go before the proposed ECA Bill becomes law. The public comment period will run through the end of January, with public hearings taking place in February. Also hanging over the entire process is a whiff of potential government change in 2018, following the election of Cyril Ramaphosa as new ANC leader, and putative South Africa President in the 2019 elections. A new executive may not share the current government's approach to restructuring the ICT market.

There are other options, from using the carrot of 4G spectrum to get operators to invest in under-served areas, to establishing a WOAN to compete with existing operators, with access to spectrum at preferential terms. An alternative player such as RAIN, Liquid Telecom or even Telkom SA could provide the foundation for a wholesale network. Ultimately, this is a case where a dexterously applied scalpel may be more effective than an indiscriminately wielded policy hatchet.

For the sake of all of Africa, one can only pray that South Africa gets this done right.

— Guy Zibi, Principal, Xalam Analytics

.jpg?width=100&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=400&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

_(1)_(1).jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

_(1).jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

_(1).jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.jpg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)